Nature Notes: Snowy Owls on the Prowl

By Dan Scheiman, PhD, Staff Ornithologist/Visitor Engagement Specialist

Now that the snow is flying, so too are Snowy Owls. This highly mobile species breeds and winters further north than any other owl. Most people encounter them only when the birds have dispersed far south of their arctic breeding range. Indeed, the causes and patterns of their movements are not understood with certainty, though decades of banding, telemetry, and satellite tracking efforts, in conjunction with environmental data, are shedding new light. Project SNOWstorm is a global collaboration of scientists, banders, and wildlife veterinarians, seeking to better understand this species of conservation concern, and turn science into action to save the species.

© Christine Blais-Soucy / Snowy Owl Project

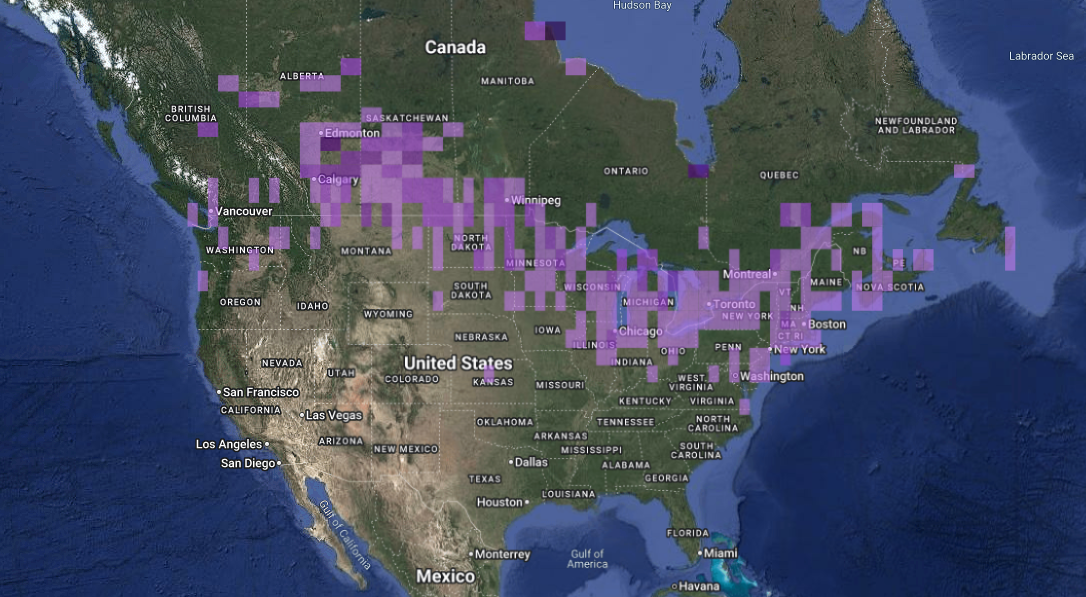

Generally, it is the young of the year that move further south than adults in winter, with some dispersing south every winter. When prey, such as lemmings, voles and ptarmigan, are plentiful, females can lay more eggs (up to 11) and pairs raise more young. More young means a larger and often more southerly “irruption” of Snowy Owls out of the arctic and into southern Canada and the Lower 48. Exactly when an irruption will occur is hard to predict and not as cyclical as once thought. The winter of 2013-14 was a really big one, with birds found as far south as Florida and even Bermuda! This winter is a more modest movement; so far the southern edge is roughly a northwest-southeast line from Alberta to Virginia.

Adults, meanwhile, are capable of spending the winter in the long dark, cold of the Arctic. They may move long distances, often east-west and across continents in search of food. Some live on the sea ice where they hunt seabirds and ducks along the edge of open water. When time to breed, they may again move long distances, congregating where food availability is high.

Snowy Owls are open country birds. When not in the arctic, they can be found hunting over prairies, marshes, farm fields, coasts, and even airports and towns. It is always exciting to see one! Keep an eye out for a white lump amidst the corn stubble, atop a power pole, or amongst the boulders of a jetty. Always keep a respectful distance, keep your voice down, move slowly, and watch for signs you may be causing stress, such as wide eyes or movement away from you. Never bait an owl to get a closer photo, and do not use tour companies that bait owls. This applies to all owl species. Posting an owl’s exact location might cause a crowd and increased disturbance, which is why some social media groups forbid it. Though they are probably not starving as once thought, they do need rest during the day and freedom to hunt when hungry.

Not all Snowy Owls that come south will survive, of course. Mortality in young, inexperienced birds generally is high. When closer to humans they are at greater risk of car collisions, power line electrocution, rodenticide poisoning and avian flu. Climate change and habitat loss further threaten them and their arctic food web. Snowy Owls have declined by over 30% over the past 25 years, with the global population estimated at fewer than 30,000 adults.

If you see an apparent sick or injured owl, call a licensed wildlife rehabilitator or your state’s wildlife agency. Some birds are lucky enough to be rehabbed and released. A few may end up as educational birds if they cannot fully recover.

Whether glimpsed on a windswept shoreline or perched quietly over an open field, Snowy Owls are a powerful reminder of the connections between the Arctic and our own landscapes—and of the conservation efforts to ensure they remain part of both.

Mark your calendars for Owl-O-Rama, March 6-7, 2026

Two days exploring Door County’s owls—their hunting adaptations, behaviors, and how we can help protect them!

Owl Prowl, Friday, March 6, 6-8:30 pm: Join a Ridges Naturalist at The Ridges Nature Center to learn about owl species that call Door County home. Then, head out on a local trail to hear them calling to one another! Meets at the Cook-Albert Fuller Nature Center, must have vehicle to drive to Prowl location.

Fee: $10 | Members receive a 20% discount; Pre-registration is required.

Eastern Screech-Owl Nest Box Workshop, Saturday, March 7, 12:30-1:30 pm: Head over to The Ridges Workshop to build Eastern Screech-Owl nest boxes to take home and hang in your backyard. A Ridges staff member will provide you with all the materials you need to assemble your nest box. Note: The nest box building portion of the workshop includes hammering and the use of power tools in an indoor space.

Fee: Public $50 | Members receive a 20% discount; Pre-registration is required.

Open Door Bird Sanctuary Meet and Greet, Saturday, March 7, 1-3 pm: Stop by The Ridges Nature Center for a fun, family-friendly experience with live birds of prey from Open Door Bird Sanctuary! This free event offers an opportunity to see owls up close and talk with ODBS staff who will be stationed throughout the Nature Center.

Free Program. Donations appreciated!

Photography Exhibit: Experience the striking owl photography of Tony Chapa in The Ridges Gallery. A Northeast Wisconsin artist, Tony’s work meticulously captures the beauty and individuality of owl species found in Wisconsin and Minnesota.